The reasons to drink pechuga during the holiday season are plentiful; beyond the literal, winking notion of enjoying your holiday turkey in alcohol form, pechuga is a style of mezcal widely associated with celebration, gatherings, festivities, and family.

A BOTTLE OF PECHUGA CANNOT BE CLOSED

For mezcal lovers in the United States, the winter holidays are an intuitive time to share a bottle of mezcal de pechuga – the style of mezcal most often associated with the inclusion of fruits, spices, and (notoriously) a raw turkey or chicken breast incorporated into the still.

In Spanish, pechuga means breast, and again the literal significance seems obvious, i.e., the breast of the poultry; however, the term arguably carries a double meaning: the breast as the home of the heart and of feelings. Much as Shakespeare’s Romeo refers to the heaviness of his breast as he yearns for Juliet, pechuga is often seen as a mezcal that carries and reflects powerful emotion. As mezcal writer Noah Arenstein notes, “some of the best [pechuga] are deeply personal expressions of a particular producer or village.”

In Spanish, pechuga means breast, and again the literal significance seems obvious, i.e., the breast of the poultry; however, the term arguably carries a double meaning: the breast as the home of the heart and of feelings. Much as Shakespeare’s Romeo refers to the heaviness of his breast as he yearns for Juliet, pechuga is often seen as a mezcal that carries and reflects powerful emotion. As mezcal writer Noah Arenstein notes, “some of the best [pechuga] are deeply personal expressions of a particular producer or village.”

A member of the Cortés family—the mezcaleros known for creating the iconic labels Agave de Cortés, Nuestra Soledad, and El Jolgorio—once told me of an elderly mezcalero ancestor who awoke one morning as though struck by lightning, invigorated and full of joy, and began dancing about the family palenque (the Oaxacan term for a rural distillation site). He called for his family to come and help him, and together they slaughtered a bird, harvested fruits and spices, and produced a stunning batch of pechuga mezcal. It was to be his last work, as he passed away mere days later, leaving behind one final, beautiful spirit for his family to share in remembrance.

Historically, pechuga were often produced for special, even monumental occasions. Batches may be distilled for baptisms, weddings, memorials, Dia de los Muertos, town celebrations…gatherings of all sorts. I’ve heard it said, “you can only distill pechuga when you have the feeling.” I’ve also heard it said, “a bottle of pechuga should not be closed.”

The party must go on.

Pechuga doubles down on the romance, the heritage, the spirituality, and the cultural significance that has attracted so many passionate enthusiasts around the world. It captures the imagination, undeniably. But, as producers and the companies increasingly investing in the category (including those appropriating it) have learned about mezcal in general, that romance is deeply marketable. With increased access, the mysterious pechuga has become even more misunderstood—sometimes even contentious. Generalizations abound, and history gets muddy fast.

So, grab yourself a veladora or a copita or a tumbler full of agave spirit, and let’s unpack a bit of what we do know about the season’s finest destilado….

THE OCCASION OF PECHUGA

Growing up, when Graciela Ángeles Carreño and her father, the late Don Lorenzo Ángeles Carreño, of Real Minero would produce mezcal de pechuga, it was an event for the whole family.

“We would notify my mother, so that she, in turn, would sacrifice the chicken and prepare all the instruments for us,” she says. “My family would buy the fruits together in the market. The fresh fruits are the ones that dictate the times in which we can make the drink.”

Local traditions play a major role in pechuga’s production. In some communities, different seasons’ harvests equate to different seasonal recipes throughout the year; in others, such as Graciela’s hometown of Santa Catarina Minas, it might be a closely guarded village or family heirloom. “Our recipe, never written down, has been memorized and passed down from generation to generation,” says Graciela. “The recipe that we currently have was taught to me by my dad and, in turn, I taught it to [my brother] Edgar. We only produce this mezcal two or three times each year.”

Though pechuga in the popular imagination is often specifically associated with celebrations and gatherings, the truth is much less cut and dry.

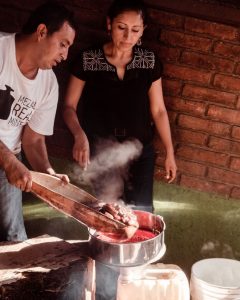

In some instances, production itself is an occasion. “While we wait for the first drops of mezcal to fall,” describes Graciela, “a broth is prepared with the rest of the chicken, which all of us who are in the palenque have for dinner. We sit together in the silence of the palenque, in the darkness of the night, with the joy of doing something special.” Gonzalo Martinez Sernas, of Macurichos, explains that in his community of Santiago Matatlán, pechuga was indeed “ceremonial mezcal. It was made for certain occasions and specific dates, offered to our ancestors, and at special parties it was shared with guests.”

However, in parts of rural Puebla—just north and west of Oaxaca—pechuga holds a very different set of traditions. Rather than raw protein, many producers incorporate their state’s most famous traditional dish—mole—and take a far more direct culinary approach to the spirit; in this case, spirituality takes a back seat to flavor, and the pechuga is less a sacred expression than an agricultural one. “The dream of many mezcaleros is to be able to sell their seasonal mezcal, as well as their corn, pumpkin, beans, and many other things, to support their families,” explains Erick Rodriguez of Pal’alma. This approach to pechuga is unique from family to family as well. Some popular producers sauté the chicken in a stock pot with mole poblano before adding it to the still; when maestro mezcalero Sergio Salas of Tlamati distills his pechuga, he collaborates with his wife, community chef Jazmin Poncé, who variously prepares meats such as rooster and quail with mole verde or adobo poblano for the spirit.

In other instances, pechuga-style mezcal might be used as a curative. Another maestro in Puebla, Asunción Matilda Vargas (also of Pal’alma), has long produced mezcal distilled with rattlesnake (for personal use) which he swears by as a cure-all for common illnesses, and the origins of the notorious gusano, or worm, in mezcal likely is a vestige of rural virility enhancement in booze form. Classic.

SO…WHICH IS IT?

The origins of pechuga are unclear. As American mezcal advocate Alvin Starkman explains, “so much of it has to do with oral histories, and people’s recollections go back only so far.”

However, in 1910, the historian Manuel Martinez Gracida noted the popular tradition of pechuga in his Los Indios Oaxaquenos y Sus Monumentos Arquelogicos on his local community of Ejutla, Oaxaca: “To obtain the ‘pechuga’ mezcal, so esteemed by many people, the pot…is filled with common mezcal, and immediately a leg of lamb or a chicken is added – quartered – as well as a long plantain, raisins, almonds, sugar, and sometimes pineapple and a little anise.”

Gracida’s description brings several modern misleading generalizations about pechuga’s production into consideration.

One, the method most often described for making pechuga, especially in English-language marketing materials, involves producing mezcal by cooking the agave, milling it, fermenting it in open-air containers, and finally distilling it twice in copper pots, then using that twice-distilled mezcal—itself a finished spirit—and redistilling it a third time with protein, fruits, and spices. While that method may be the most widespread today, when Gracida refers to “common mezcal,” he is referencing what’s also known as “ordinarios”—the typically lower-ABV results of the first distillation run in mezcal. Thus, the additional ingredients can also be added on the second distillation, not always just the third.

It is rare, but not unheard of, to find pechuga on today’s market which is distilled twice in pot stills, rather than three times, and the results can be distinctly different. A prime example is Gonzalo Martinez Sernas and family, of Macurichos, who distill their pechuga just twice in clay pot stills. Their pechuga also stands out for a second notable production point underscored by Gracida’s 1910 text: while turkey and chicken are by far the most common proteins added to the spirit, other animals are not uncommon. Gracida references lamb; Macurichos is made with rabbit (conejo).

A third intriguing contrast with modern pechuga generalizations can be found in Gracida’s brief paragraph. Most often, we describe maestros adding their fruits and spices and breast to the spirit by suspending them in a sack or basket inside the still, much like many gin producers suspend their botanical basket. As some narratives go, the fats and juices from the suspended fruit and meat drip down into the distilling mezcal; others say, more fancifully, that the alcohol’s vapors pass through the raw protein, as though it were a filter made of flesh. Whatever your take on the suspension method, there is again more diversity to the tradition. Gracida describes the ingredients being added directly to the bubbling mezcal inside the still, and many maestro mezcaleros who are not using copper alembic pot stills today will likewise simply dump their ingredients—be it rabbit or lamb, chicken or mango, flowers or citrus, mushrooms or marijuana—directly into the juice, steeping them like tea or a big boozy stew, as they’re distilled in a pot made of clay, wood, or copper.

The point is that none of these rules are hard and fast. Within our deep, diverse, and unparalleled agave portfolio here at Skurnik Wines & Spirits, we have examples which touch upon all these techniques, and though some maestros may disagree about the methods, they are all deeply valid and historic examples of pechuga. Oh, and they’re all delicious.

SO…WAIT. WHAT IS IT?

Of course, this all means it’s rather hard to settle on one, easy definition of “pechuga”.

It means breast, but it doesn’t have to. It means poultry, but it doesn’t have to. It means celebrations, but it doesn’t have to. It means distilled three times, but it doesn’t have to. It means suspended botanicals, but it doesn’t have to. This is getting confusing!

Does it even have to have meat, or can pechuga be vegan?

As you might expect, people get passionate about defining pechuga. (“Only the original turkey, chicken, or rabbit pechuga is true to Oaxaca,” Gonzalo tells me, in his charmingly gruff way. “Everything else is just marketing inventions.” Per that 1910 text, I tell him, maybe we can allow for some lamb, too.) The debate is alive, and important. As with every aspect of the categorization of mezcal, the impact of creating definitions can have real consequences, and in unforeseen directions. Some people may be boxed out of their own heritage; some traditions may be uprooted; still others may be excluded when exploring new ideas.

“About 15 years ago,” says Graciela, “there was an attempt to define what mezcal de pechuga is, and to propose it as another category of mezcal in the NOM-070…however the proposal did not bear fruit. Time passed, and new things like the ones we see now began to emerge more frequently on the market.” A menagerie of new exotic animals are being used in experimental pechuga each year—there are multiple brands producing Iberico ham pechuga at this point—while other communities who have historically used diverse wildlife are being critiqued for exotifying the category.

Some brands have indeed begun to market products as vegan pechuga. For some (especially staunch vegetarians), this is a welcome alternative, a chance to access mezcal distilled with unique, added flavors. For others (especially staunch traditionalists), this is a misrepresentation of both pechuga and the parallel tradition of distilling mezcal with added fruits, roots, herbs, or spices, but no meat (which was likely not historically referred to as mezcal de pechuga). Mezcal advocates land on both sides of the coin—some say that pechuga with protein shows off the fruits and spices more than the meat to begin with, so the distinction is subjective, while others argue that the specific texture and umami notes of the protein are critical to the category.

“Is a mezcal de pechuga a fruit punch?” asks Gonzalo of Macurichos. “When trying it, you should feel the flavor of the maguey, balanced with the fruits and the thickness of the turkey fat. There are families that continue to protect this tradition, families that were born, live, and love this drink that our ancestors inherited from us.”

“I am in favor of experimenting to continue the journey,” Graciela explains, “but there must also be limits. It’s like thinking about cocktails. Classic cocktails are just that, classic; but everyone recognizes that, and starts from them to be inspired by new things based on the classics. Creation and reinvention should be based on a deep sense of belonging. Mezcal represents the history and tradition of many towns, and among the mezcal towns we always respected each other, until the merchants appeared. We are in the second wave of the reification of mezcal.”

TRADITION…ISN’T THAT WHAT THE HOLIDAYS ARE ALL ABOUT?

Amid all these swirling traditions and changes, myths and generalizations, amid the deep romance of heritage and spirit, one truth of all this remains clear. It’s a simple one, and it’s our message for the season.

At its heart, mezcal—pechuga and otherwise—helps us to come together. All of us. It helps some people hold onto tradition, and it helps other people discover traditions they didn’t know they needed. It helps us to hang onto one another, to celebrate our love and connection, to light our laughter and to dig into deep feelings. Maybe this year it helps us overcome the divide of election debates or inspires us to welcome someone new to our family table this holiday season. Mezcal is for sharing, and all of it, including pechuga, is for celebration.

Happy Holidays, 2022!

THE PECHUGAS

- Produced by Maestro Mezcalero Edgar Gonzalez Ramirez in San Cristobal Lachirioag

- Distilled from 100% Espadín (Agave angustifolia)

- Cooked in a conical earthen pit, milled using a traditional stone tahona, and fermented in open-air wooden vats

- Distilled three times using traditional wood-fired copper pot stills

- Addition of wild pineapple, blackberries, bananas, wild apples, plums, cinnamon and occasionally rice–plus a raw turkey breast–on third distillation

- Rich and dense, with autumnal notes such as almond, baked apple, grilled pineapple, basil and chocolate

- 48.1% ABV (ABV varies batch to batch)

Destilado de Agave, Pechuga, ‘Deer Traditional’, Tlamati

- Maestro Mezcalero: Balbino & Sergio Salas

- Collaboration with chef Jazmín Ponce

- Produced in San Miguel Atlapulco, Puebla

- 100% Papalométl (Agave potatorum)

- Cooked in a conical earthen oven; Milled by hand using wooden mallet & canoa as well as with a small mechanical grinder

- Fermented with ambient yeast and spring water in stainless steel tanks

- Distilled three times using a traditional copper pot still

- Addition of venison (deer) and adobo spice on the third distillation

- Wet moss, old leather, fresh bricks, cumin, chili, anise, on the nose; palate bursts with fruit such as plantain, strawberry, and dates, alongside distinct umami mushroom notes, roasted parsnip, sea salt, and a bit of Cadbury’s crème egg. Delightful and a bit too easy!

- 46.1% ABV (Alcohol may vary batch to batch)

- Only 73 bottles produced in this batch

Destilado de Agave, Pechuga, Real Minero

This one of-a-kind release represents a unique intergenerational collaboration. Before he passed away, the family maestro, Don Lorenzo, completed two of three distillations of what would be the last of his legendary Pechuga. With his tragic passing in 2016 the process stalled, but not before he imparted the family recipe to his daughter Graciela. Now, years later, Graciela and her brother Edgar have completed this final batch of Pechuga, distilling the agave a third time with the addition of fruits (such as banana, apricot, raisin, apple and pineapple) and spices (including cinnamon, almond and anise) and the raw breast of chicken.

This is the first Pechuga from the family in many years, a posthumous work of art which blurs the boundaries of time, heredity and even mortality. Pechuga mezcales were historically thought of as a deeply spiritual mezcal, and there can be no better example of that tradition than this release from Real Minero. We are honored to share it. 47.04% ABV

Mezcal, Espadin ‘Destilado con Cacao’, Macurichos

- Produced by Maestro Mezcalero Valentin Martinez Sernas, in Santiago Matatlán, Oaxaca

- Made from 100% Espadín (Agave angustifolia) matured between 6–12 years

- Agave cooked in an earthen oven, milled using traditional stone tahona mill, then fermented in wood vats

- Distilled twice using a traditional clay pot still

- The second distillation sees the addition of fresh Oaxacan cacao made by Gonzalo’s sisters

- Rested 21 months in glass

- Hot cocoa on the nose; the palate is graceful and light on its feet, with pink peppercorn, jasmine, and herbs; light but pronounced smoke gives a mature backbone to the notes of cacao and the finish is salty and earthy

- 48.8% ABV (Alcohol will vary batch to batch)

Mezcal, Espadin ‘Conejo – Rabbit’, Macurichos

- Produced by Maestro Mezcalero Gonzalo Martinez Sernas in Santiago Matatlán, Oaxaca

- Made from 100% Espadín (Agave angustifolia) matured between 6–12 years

- Cooked in an earthen oven, milled using traditional stone tahona mill, then fermented in wood vats

- Traditional pechuga distilled using a traditional clay pot still

- The second distillation sees the addition of rabbit saddle (conejo) plus apple, cinnamon, banana, pineapple, orange and wild fruit

- Rested 26 months in glass

- The nose is bright and fruity—green apple & banana show prominently with hints of cherry and passionfruit; the palate has stunning notes of jasmine, cilantro, pink peppercorn, and fresh linen alongside roasted pineapple skin

- 48.36% ABV (Alcohol will vary batch to batch)

Sotol, Sotol Carnei, ‘Venison Pechuga’, Flor Del Desierto

- Produced by Master Sotelier José “Chito” Fernandez Flores

- Sotol Sierra is a “pechuga”-style sotol made from 18–22-year-old, 100% Dasylirion weeleri wild harvested from the forests of the Madera Mountains in Chihuahua

- Cooked in shallow pits fueled by willow and oak, the plants are then shredded by axe and knife and open-air fermented for 7–9 days in pine wood tanks

- Distilled three times in traditional copper pot stills

- The third distillation introduces a number of botanicals including star anise, orange, raisin, apple, and walnuts; perhaps most notably, a raw cut of venison (deer) is hung in the pot still’s upper chamber, for traditional reasons both aesthetic and spiritual

- 51% ABV

Sotol, Sotol Cascabel, ‘Snake Pechuga’, Flor Del Desierto [Black Bottle]

- Produced by Master Sotelier Don Gerardo Ruelas

- Sotol Cascabel is a “pechuga”-style sotol made from 18–22 year old, 100% Dasylirion leiophyllum wild harvested at low elevation in the Coyame Desert

- Cooked in shallow pits fueled by willow and oak, the plants are then shredded by axe and knife and open-air fermented in pine wood tanks

- Distilled three times in traditional copper pot stills

- The third distillation introduces fresh rattlesnake meat at about 3 grams per liter of sotol

- Aged for 90 days in 40-year-old neutral oak casks

- A unique spirit with a complex character that includes citrus, quince, and salty pine resin rounded by the natural sweetness of roasted piñas and the soft vanillin of oak age, all wrapped up with a long, elegant mineral finish

- 48% ABV

Raicilla, Pechuga, Estancia Distillery

- Maestro Raicillero Alfredo Salvatierra

- Produced in La Estancia de Landeros, Jalisco

- 100% Maximiliana (Agave maximiliana)

- Cooked in adobe oven (like a pizza oven)

- Fermented entirely in amphora clay pots

- Distilled three times using traditional copper pot stills

- Addition of toasted pumpkin seed, quince, apple, plum, lemon leaves, toasted almonds, chamomile, hibiscus, nanci, golpe, lima peel, rose castilla, orange blossom and raw turkey breast on third distillation

- 48% ABV

- Produced in Santiago Matatlán, Oaxaca

- 100% Espadín (Agave angustifolia)

- Practicing organic agriculture

- The agave is cooked in a horno (conical earthen oven), milled using horse-driven stone tahona, and naturally fermented in open-air wooden tanks called tinas

- Distilled using traditional copper pot stills

- The second distillation sees the addition of pineapple, lime, orange, plantain, apple, pear, and raw turkey breast

- 48% ABV (Alcohol will vary with each batch)

Mezcal, Pechuga Navidena, El Jolgorio (BB)

Traditional mezcal forms an important part of rituals, ceremonies and festivities—known as “jolgorios”—in the rural and indigenous Zapotec villages of Oaxaca, Mexico.

Created by the Cortés family, El Jolgorio is widely acknowledged as one of the finest collections of agave spirits available. The ever-changing lineup of mezcales represent the most rare expressions the family bottles: wild, semi-wild and cultivated agaves, rare pechuga distillations, and small batches rested in glass for three, six, or as much as eighteen years before release.

From batch to batch, an individual variety of agave will generally be sourced from different mezcaleros, in different regions, reducing the pressure put upon any one community’s agave population and spreading the financial benefits among families all over Oaxaca – but the unmatched quality of El Jolgorio mezcales remains the same.

Dry Gin, Artesanal (Green Label), Abrojo

- Gin distilled from the spent agave from mezcal production and local botanicals in the district of Tlacolula in Santiago Matatlán, Oaxaca

- Maestro destilador Gonzalo Martinez

- After it’s use in his family’s mezcal production, spent agave fiber (bagasse) is remilled by hand using a large wooden mallet and long wooden canoe

- Combined incrementally with spring water and refermented using only wild yeast

- Distilled once on a copper still (Artesanal) before 15 locally sourced botanicals are added in the second distillation

- Some of the botanicals include juniper, hoja santa (Mexican pepperleaf), basil, cinnamon, guava, orange & lime peel, eucalyptus, lemon grass, and mint

- Rested in glass for one year before bottling

- A bright nose of lime oil, green cardamom, and yellow bell pepper is underscored by earthy, sweet molasses and roasted agave piña. The waxy, verdant palate is replete with cilantro, coriander seed, and tarragon, with a lasting finish of orange peel and gooseberry

- 45% ABV

Dry Gin, Ancestral (Blue Label), Abrojo

- Gin distilled from the spent agave from mezcal production and local botanicals in the district of Tlacolula in Santiago Matatlán, Oaxaca

- Maestro destilador Gonzalo Martinez

- After its use in his family’s mezcal production, spent agave fiber (bagasse) is remilled by hand using a large wooden mallet and long wooden canoe

- Combined incrementally with spring water and refermented using only wild yeast

- Distilled once on a clay still (Ancestral) before 15 locally sourced botanicals are added in the second distillation

- Some of the botanicals include juniper, hoja santa (Mexican pepperleaf), basil, cinnamon, guava, orange & lime peel, eucalyptus, lemon grass, and mint

- Rested in glass for one year before bottling

- This juniper-forward expression is complemented by fresh cucumber skin, sea salt, and tapioca root on the noose. The palate confidently displays lemongrass beautifully married with hues of clay, lemon verbena, green peppercorn, and a finish of pine resin and spearmint. Don’t be surprised when you find yourself sipping this gin neat.

- 50% ABV