Is there any better time of year to be in Japan than October? We don’t think so. The punishing dripping heat of summer subsides to brisk fall weather. Foraged mushrooms begin to appear on restaurant menus. The delicate Pacific saury fish, known locally as sanma, is caught and grilled whole. And of course the fruits of the fall harvest are in. Freshly harvested buckwheat is ground into flour for shin-soba, the noodles at their most delicate, nutty and delicious for a fleeting few days in the fall. Rice is never as sweet or perfectly textured as the fresh crop arriving in the fall. And not by coincidence fall is the best time of year for sake. Stock laid down from the previous winter that has been maturing for several months is released in September; the volatile youthful energy becomes focused into fresh sake with depth and elegance. And with the rice harvest arriving and temperatures cooling the majority of breweries begin to restart operations after lying dormant throughout the summer.

With the confluence of new sake releases and the beginning of the brewing season the industry has designated October 1st World Sake Day, and officially the start of the season for making sake and shochu. While some breweries have set themselves up to brew all year round, the common yearly schedule of a brewery is set around the rice harvest. In addition to the advantages of making sake when rice is at its freshest, the simple logistics of staffing a brewery also comes in to play.

While the history of each sake brewery is unique they are often tied to a single family. Many breweries were started centuries ago by rice merchants looking to add value to rice and make use of any extra inventory. Before the advent of automation and modern machines making sake was a labor-intensive endeavor requiring dozens of sets of hands. For many farmers in feudal times going to work in a sake brewery for the cold months as their rice paddies lay dry and dormant was a much-needed chance to earn extra money. Every autumn entire teams from single villages would agree to work at breweries for the sake making season, sometimes making trips across the country if the money was right. They would start after harvest, work through the winter as the cold temperatures allow for clean and consistent fermentation, and return to their villages in the spring in time for planting.

Our partner breweries have been shaking off the cobwebs and getting ready as well. Not surprisingly there are many religious and cultural traditions tied to sake making. All brewers will either make a trip to a shrine whose spirit can bring good fortune in the sake season, or have a Shinto priest bless the brewery itself each year.

In addition to spiritual renewal, the breweries get a physical renewal as well with a thorough scrubbing to start the season. The not so exciting secret of great sake making is that rigorous cleaning regimens make for better results, and it is often said that 90% of the work in sake breweries is keeping things spic and span.

While many breweries have milled rice delivered Kirinzan Brewery in Niigata sources all the rice for their sake from their local farming cooperative and the brewery team works side by side with the farmers during harvest. In addition to the advantages of keeping things local, there is a greater sense of responsibility on all sides since they will all be drinking sake from that rice.

After cleaning and harvest breweries will be getting down to the nitty-gritty of brewing. Toji brewmasters will begin to familiarize themselves with the particular moisture content of this year’s rice crop and will adjust their soaking and steaming times accordingly. Like its cousin beer, sake aims for consistency year after year, and it is part of a brewmaster’s craft to adjust their brewing process to the variations in rice quality and availability each year. Commonly breweries will make their less expensive sake at the beginning of the season in order to fully master the peculiarities of the new crop and to get the team in practice for the more technically difficult and expensive ginjo grades of sake. Those are commonly made once the season is in full swing in January and February.

By April and May operations often start to wind down, a final year-end cleaning happens and rice seedlings are planted once again. Even breweries that are able to operate year-round due to advance air conditioning will shut down for a period in July or August for equipment maintenance and cleaning. Sake is often laid down to store and age in tanks for a couple months, eagerly awaiting when they will be enjoyed in the cool autumn weather.

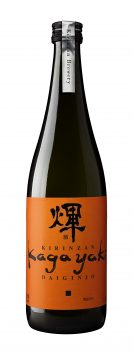

Cover Photo is of Kirinzan in Niigata.

Kirinzan ‘Classic’ Futsu-shu

While breweries love to showcase their premium ginjo styles Kirinzan take immense pride in their entry level ‘futsu-shu’ meant for everyday drinking. They use Gohyaku Mangoku and Koshi Ibuki sake rice polished to 65%, beyond requirements for even the premium honjozo grade. Made in the house style, it is dry, clean, light bodied, well balanced. Notes of hazelnut and toasted rice that makes it excellent both chilled or gently warmed.

Kirinzan ‘Kagayaki’ Daiginjo Genshu

Elegant and delicate, the Kirinzan Daiginjo Genshu contains multitudes of flavor. Fresh and lively with mint and lemongrass. Notes of ripe apricots tempered with touches of anise, fennel and herbs adds complexity to this rich sake. Local Koshi Taneri rice milled to 40% remaining. After brewing the toji has skipped the standard step of a water addition leaving the resulting sake layered and dense with flavor.

Akishika Junmai Muroka Nama Genshu

A stout, robust and incredibly dry sake, prominent notes of black walnuts and caramel shading into spicy flavors of allspice and clove, the rich and spicy structure responds well to aging, flavor gaining depth and richness. Sake improves after opening growing mellow and gaining sweetness for days or weeks.

Brewery is located in the mountains between Kyoto and Osaka among terraced rice paddies. All of the rice used is locally grown by farmers committed to “bio-dynamic” (junkan) farming practices. Yamada Nishiki polished to 60%.

Bijofu Junmai

Defined and precise, the Bijofu Junmai is a sake with zip, spice and drinkability. Not a heavy or earthy Junmai, this sake is light and fresh, faint notes of passion fruit and freshly crushed mint leaves. Matsuyama Mii rice milled to 60%.

Umenoyado Aragoshi Umeshu

Aragoshi means ‘roughly pressed.’ The Aragoshi Umeshu containers 21% freshly squeezed plum nectar by volume. It retains the natural pulp and sweetness of specially selected, hand-washed ume plums. One of the finest and most distinctive plum wines produced today.

Umenoyado Aragoshi Yuzushu

Aragoshi means “roughly pressed”. Fresh whole yuzu fruit was squeezed into this sake with a total juice content of 21% and plenty of natural pulp. The natural citrus oils and juice of handpicked fruit give an extremely bright example of yuzu. Great chilled, on the rocks, or (!) mixed in a cocktail. 8% ABV.